THIS POST CONTAINS SPOILERS!

I first read about Snowpiercer late in 2013 and quickly recommended it to fellow dystopian film lovers. Despite small concerns that the train-functioning-as-metaphor-for-capitalism was gimmicky and simplistic, I enjoyed The Host (one of Joon-ho Bong’s previous films) and was intrigued by the photographic stills I’d seen online. The few pages I could find of Le Transperceneige (the comic the film is based on) looked exquisite. Suffice it to say, I had high hopes as I walked into the almighty Civic on Friday night.

Thankfully, Snowpiercer delivered everything I’d hoped for and more, and I can’t stop thinking about it (to the detriment of my university work). The film isn’t simplistic, as I’d feared, but an intelligent critique of capitalism and the behaviour it encourages.

The Self-Made Man

Snowpiercer reveals how tempting the “self-made man” narrative is in capitalist society. In my experience, those who come from difficult beginnings often forget about it once they’ve moved to “high places”. Self-made men and women will, however, evoke stories of difficult beginnings when it affirms the meritocratic mantra that working hard will lead to success, regardless of the environment into which you are born. “The world’s your oyster!” says the meritocrat. Nothings who become somethings prove the meritocrat right: “If you weren’t so lazy, you could make it, too!”

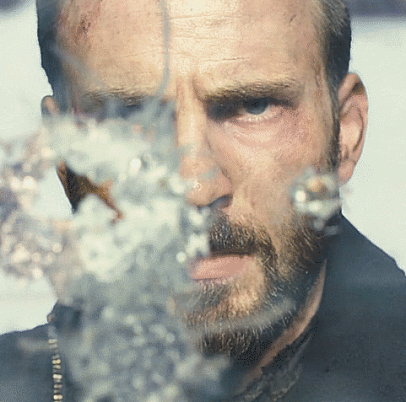

In Snowpiercer, Wilford uses the self-made man narrative to tempt Curtis into compliance. “You’re the only person who has ever travelled the full length of the train”, Wilford congratulates Curtis upon his arrival in the engine room, before rewarding him with a comfy seat and a plate of steak.

Wilford is full of praise and admiration for Curtis: the trek to the front wasn’t easy and audiences, having followed him all the way, know it. We also know that Curtis didn’t get there alone (it was a collective effort and many sacrificed their lives in the process), but this is quickly forgotten as Wilford’s respect for Curtis leaves him feeling like an individual hero, a success, and an equal. If Yona hadn’t step in when she did, I wouldn’t be surprised if Curtis fell for this narrative. It’s very tempting. Let’s not forget, though, that for every successful person, there’s a support team; teachers, parents, siblings, friends, and lovers behind the scenes spurring us on.

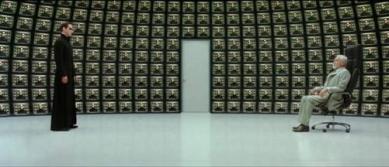

This scene will not only remind you of Neo meeting The Architect in The Matrix Reloaded, but also of Truman speaking to Cristof – the creator – in The Truman Show. (And, just to add intertextual magnificence into this, Wilford and Cristof are both played by Ed Harris!)

Capitalism as an Ecosystem

Snowpiercer also critiques our tendency to think about the economy as natural (not a human construction). In the aforementioned final scene, Wilford refers to the organisation of the train as an “ecosystem”. This ecosystem comes to its natural equilibrium when each carriage has the right amount of people in it, these people know what’s expected from them, and interaction between carriages is as it “ought to be”. Wilford describes how the equilibrium is maintained. Like a pressure valve, short bursts of violence are allowed (manufactured, even) so the train’s occupants can ‘let off steam’, thus preventing a larger display of political resistance gaining momentum. Any disruptions to the ecosystem are therefore accounted for as natural ebb and flow. Interestingly, the global financial crisis was spoken of in this way (“it’s just the system sorting itself out”, “boom and bust, duh!”), and the damage to people’s lives brushed over.

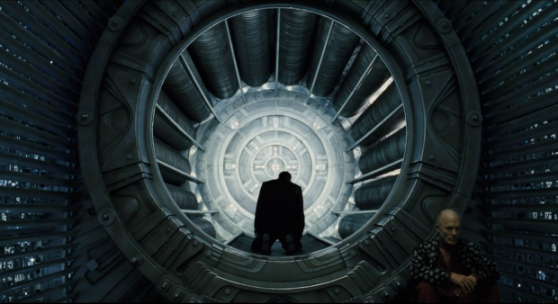

We watch Curtis become convinced by Wilford’s ecosystem metaphor, and, even more so, when he collapses onto his knees in the centre of the train’s engine. He is instructed by Wilford to listen. “When was the last time you were alone?” Wilford says to Curtis, “You can’t remember, can you? So, please, do take your time.”

This moment of the film is brilliant. Curtis is listening to the train’s engine – the heartbeat of the capitalist ecosystem. On its own, independent from us, capitalism is alive. We can only fall to our knees and surrender to it. However, seconds later, it is revealed that Tim (a child under 5) is working under the floor, oiling the engine. Capitalism is not naturally occurring, it is a human artifice maintained through exploitation. Snowpiercer critiques the use of ecological language and concepts when referring to the organisation of our economy.

This brings me nicely to my next point:

Political Institutions and the Environment

In policy discussions, the environment is often spoken about in the same breath as the economy, as if the two are of equal importance. Or worse, environmental protection is sidelined by the ‘more urgent’ problems facing the economy. Thus the environment is not seen as existing prior to political institutions, but merely one of many ‘political issues’ discussed by those operating within institutions. How we forget that political institutions are man-made artifices that require the environment in order to actually exist is beyond me (how long would JPMorgan or HSBC survive on Jupiter?). Regardless, it is this relationship – between environment and political establishment – that Snowpiercer explores with such sophistication.

In the film, the institution (the train) operates in isolation from the uninhabitable environment outside. This appears to refute my thesis, as the political institution has survived regardless of the environment. However, the film constantly exposes the fragility of the relationship between the two

In the end, it is not simply the explosion within the train that derails it. It is the explosion inside that causes the environment outside to shift: large sheets of snow are unearthed, crashing into the train and causing it to topple.

The environment surrounding the train ultimately destroys the seemingly “isolated” institution within the train. When Yona and Tim (the only two survivors) escape the wreckage, I half expected them to stumble across a group of human survivors (another political institution with its own social contract) that they must find their place within. This was not the case. There is a complete absence of institutions. What they see instead, and the shot the film ends on, is a polar bear. Ironically, this is the very animal at the centre of ‘economy vs. environment’ debates. As Snowpiercer suggests, the environment always wins: without the environment, we have no economy. Better start taking better care of it, then!

by Alex Edney-Browne